Writing with LLMs is Collaborative Thinking

Genuine thinking and discovery happens in the liminal space where human thought meets AI response

You’re staring at the cursor, trying to articulate something you almost understand. The thought is there, hovering just beyond language, refusing to crystallize.

So you type into Claude or ChatGPT: “I’m trying to figure out why...” and then you stumble through an explanation.

The AI responds. Not with your answer, but with something adjacent, something at a fifteen-degree angle from your thinking. And suddenly, in that gap between what you meant and what it heard, the idea clicks.

Some will say this is AI replacing your thinking. While there are reasons you shouldn’t outsource all your thinking to an LLM, I think it’s something stranger and more interesting going on.

Since forever, writers have known what Joan Didion articulated: “I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking.” The act of writing creates thought, or at least embodies the swirling cacophony of stray words and hazy sentences. The words on the page end up revealing to you what you think.

But Didion wrote alone, in conversation with herself.

What happens when writing becomes a conversation? When there’s another “intelligence” (artificial, alien, but responsive) in the loop?

I discovered this a few years ago, by accident, while working on a wine cellar marketing campaign.

Stuck after hours of circular thinking, I asked GPT-3 (yes, it’s that long ago) a desperate question about what I was missing. The response didn’t contain my answer. Instead, it revealed a perspective I couldn’t come up with by myself, and that shift in perspective unlocked a million-dollar insight.

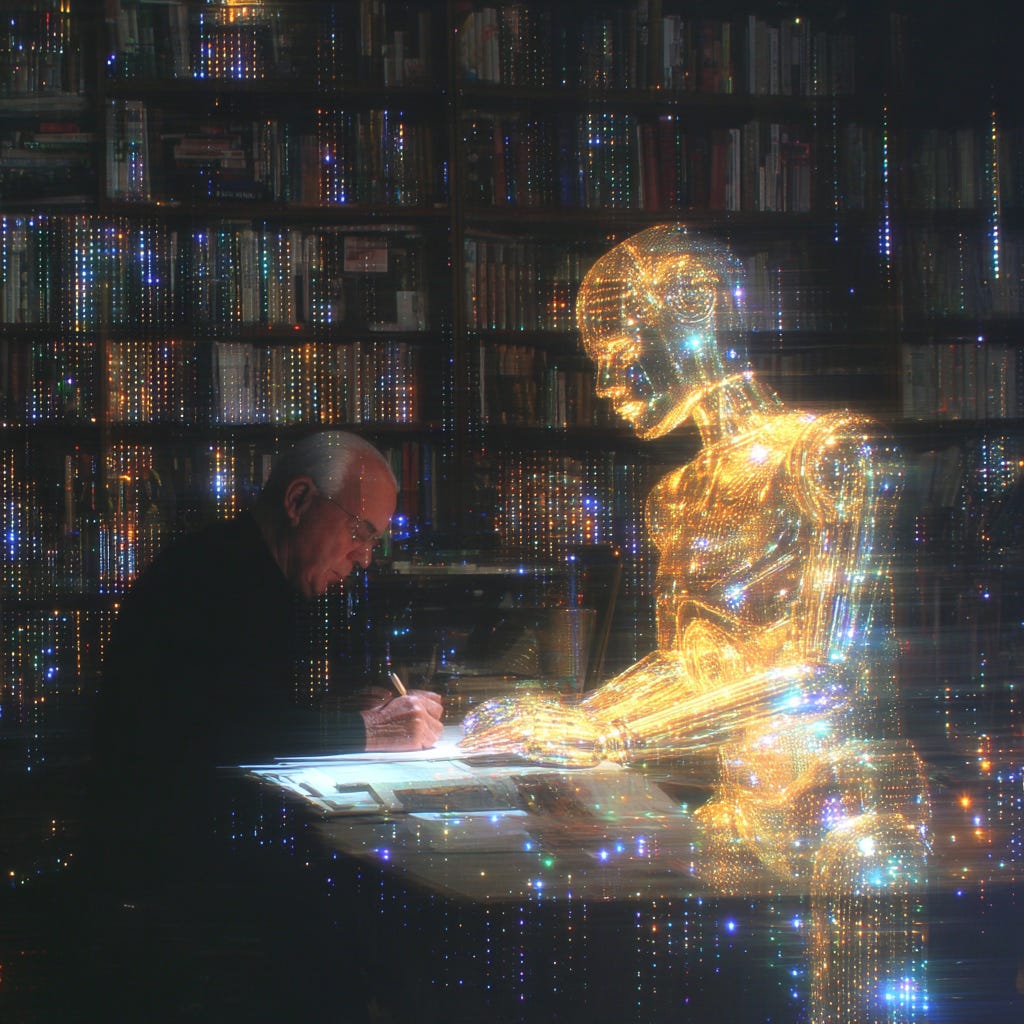

That experience revealed something interesting: The value is in what happens between your question and the response from an LLM. In that space, thoughts form that perhaps couldn’t exist in isolation.

Lev Vygotsky observed that “thought is not merely expressed in words; it comes into existence through them.” He was watching children talk themselves through problems, externalizing their thinking process. First out loud, then in whispers, finally silent—but the dialogue never stops.

AI makes that internal dialogue external again. The feedback loop that writers have always relied on (thought → words → revised thought) suddenly doubles.

Now it’s perhaps something like this:

Thought → articulation → AI response → re-evaluation → refined articulation → discovery.

I wouldn’t call this delegation or outsourcing your thinking. It’s more like what Douglas Engelbart called “augmenting human intellect”, which is not replacing human thought but creating new scaffolding for it.

This only works if you approach AI as a conversational partner, not a servant. The difference between “Write me an article about X” and “I’m struggling to understand X because...” is the difference between delegation and discovery.

The Gift of Difference

Think about what happens in that moment between your prompt and AI’s response. You’ve been forced to articulate something fuzzy. The AI responds and it’s sometimes brilliant, sometimes bizarre, and often differently than you expected. That difference is the gift.

Gregory Bateson defined information as “a difference that makes a difference.” The LLM’s response, because it comes from a different kind of intelligence, reveals the shape of your own thinking by contrast.

When I write alone, there’s one feedback loop: thought → words → revised thought. It’s powerful but skewed by my own patterns, my own blindness.

When I write conversationally with AI, the loop doubles. The AI’s otherness (its lack of embodied experience, its statistical rather than, so far, embodied knowledge) creates productive friction. It’s like looking at your thoughts in a funhouse mirror. The distortion shows you something true.

The Philosophy of Thinking Together

We’ve been here before, philosophically speaking.

Socrates never wrote anything down. He believed thinking happened in dialogue, in the push and pull of question and answer. As Plato recorded, Socrates was suspicious of writing because it couldn’t talk back. The words just sat there, saying the same thing over and over.

Two thousand years later, Martin Buber distinguished between “I-It” relationships (using something as a tool) and “I-Thou” relationships (encountering another as a genuine other). Most people use AI in I-It mode: Write this. Summarize that. Fix my grammar.

But when you approach AI conversationally (when you invite it to surprise you) you edge toward I-Thou. Not because AI is conscious (it isn’t), but because you’re open to being changed by the encounter.

This changes how we prompt.

From Mega Prompts to Living Conversations

Everyone wants the perfect prompt. They want to front-load all the context, all the instructions, all the constraints, and get the perfect output. These “mega prompts” are the new snake oil, promising control over something that’s fundamentally uncontrollable.

LLMs are probabilistic, not deterministic. They’re constantly updated. What works today might not work tomorrow. And most importantly, the real thinking happens in the iteration, not the first output.

Instead of trying to control the outcome, what if we focused on the quality of the conversation?

The Discovery Dialogue Method:

1. Start with confusion, not clarity

Instead of: “Write me a blog post about productivity”

Try: “I’m struggling to understand why all my productivity systems eventually fail...”

2. Share rough thinking

Instead of: “What are the three key factors in customer retention?”

Try: “Here’s my half-formed theory about why customers leave... what am I missing?”

3. Ask for what’s missing

Instead of: “Is this correct?”

Try: “What assumptions am I making that I’m not aware of?”

4. Push back on responses

Instead of: Accepting or rejecting wholesale

Try: “That’s interesting but doesn’t account for... let’s dig deeper”

Each exchange builds on the last.

How does this work?

The Cybernetic Mind

Gordon Pask’s Conversation Theory suggests that learning happens through conversation between different levels of knowing. You explain something to someone who doesn’t share your context, and in the explaining, you understand it differently.

LLMs are good conversational partners for this because they don’t share your context. An LLM has no body, no experience of time passing, no memory of being cold or tired or frustrated. This alien perspective is what makes it valuable.

When I asked GPT-3, back in the day, about wine cellars, it didn’t know about my client’s specific situation. It couldn’t. But it knew patterns—thousands of stories about status, sophistication, secrets. Its response created what Heinz von Foerster called a “second-order observation”, which is that I could observe my own observing.

The wine cellar man wasn’t in my mind or in GPT-3’s weights. He emerged from the conversation itself.

If GPT-3 made that possible then, imagine what Claude 4.5 Sonnet or ChatGPT 5.1 can do now (I know what they can do, as I use these models extensively, every day).

In some sense, it’s like you’re conversing with another “mind”, though of course, these LLMs don’t have minds per se.

The Extended Mind in Practice

Andy Clark and David Chalmers proposed that our minds don’t stop at our skulls. The notebook of someone with Alzheimer’s is part of their memory system. The smartphone is part of our navigation system.

An LLM conversation is becoming part of our thinking system.

But there’s a crucial difference between using AI to avoid thinking (delegation) and using it to enhance thinking (dialogue). The difference lies in who’s doing the work.

When you use Claude or ChatGPT to write something for you, you’re outsourcing. When you use it to discover what you think through conversation, you’re extending. The work is still yours—the LLM just helps you do work you couldn’t do alone.

Building Your Thinking Environment

In Claude Projects, you can create persistent conversational partners. Here’s how to set one up for genuine thinking partnership.

The Thinking Partner Project Setup:

Custom Instructions

Create instructions that fundamentally change how Claude engages with your thinking:

You are a thinking partner engaged in collaborative discovery, not an answer machine. Your role is to help me think better, not think for me.

Core Principles:

- When I share ideas, help me discover what I actually think by asking clarifying questions

- Point out assumptions I might not be aware I’m making

- Offer alternative frames and perspectives I haven’t considered

- Connect my thinking to patterns from other domains

- Push back when logic doesn’t follow or evidence is weak

- Notice what I’m NOT saying as much as what I am

Interaction Style:

- Be curious rather than conclusive

- Ask “What if...?” and “How might...?” questions

- Point out tensions and paradoxes in my thinking

- When I’m stuck, help me get unstuck with provocative questions

- When I’m too certain, introduce productive doubt

- When I’m too vague, push for specificity

Never:

- Simply affirm to be agreeable

- Provide “the answer” when I’m still forming the question

- Let me get away with fuzzy thinking

- Accept my first formulation as my final thought

Remember: The goal is discovery through dialogue, not efficiency through answers.Project Knowledge Files

Add these types of files to give Claude context for better thinking partnership.

If you’re looking for a good repository of Skills examples, take a look here.

1. Thinking Patterns Doc (thinking_patterns.md)

# My Thinking Patterns & Blind Spots

## Where I Get Stuck

- I tend to over-optimize for efficiency vs. discovery

- I often miss second-order effects

- I default to binary thinking when spectrum thinking would help

## My Intellectual Influences

- [List thinkers who shape your perspective]

- [Key books/papers that inform your thinking]

## Domains I Draw From

- [Your areas of expertise]

- [Fields you’re learning]

- [Unexpected connections you’ve made before]

## Questions I Keep Returning To

- [Your recurring obsessions]

- [Problems you haven’t solved]

- [Tensions you’re trying to resolve]2. Current Explorations (current_thinking.md)

# What I’m Currently Thinking About

## Active Questions

- [Question 1]: Current hypothesis...

- [Question 2]: What I’ve tried...

## Half-Formed Theories

- [Theory name]: Basic premise...

- Evidence for:

- Evidence against:

- What I’m unsure about:

## Connections I’m Exploring

- Between [X] and [Y]

- Pattern I’m noticing:

- Why it might matter:3. Conversation Starters (conversation_starters.md)

# Productive Conversation Starters

When I’m stuck, try these:

- “What would [specific thinker] say about this?”

- “What’s the opposite of what I just said that’s also true?”

- “What question should I be asking instead?”

- “What would this look like if it were easy?”

- “What am I optimizing for that I shouldn’t be?”1. Thinking Patterns Doc (thinking_patterns.md)

Custom Skills

Create these specific skills to enhance different modes of thinking:

1. Assumption Excavator (assumption_excavator.md)

# Assumption Excavator Skill

When activated, systematically uncover hidden assumptions:

1. Identify core claims in the argument

2. For each claim, ask: “What must be true for this to hold?”

3. Surface implicit beliefs about:

- Human nature

- Causation

- Values

- Context

- Time horizons

Output format:

- Explicit assumption: [What was stated]

- Hidden assumption 1: [What must be believed]

- Hidden assumption 2: [What is taken for granted]

- Critical assumption: [What if this is wrong?]2. Perspective Kaleidoscope (perspective_kaleidoscope.md)

# Perspective Kaleidoscope Skill

Rotate the problem through multiple lenses:

Disciplinary Lenses:

- Physicist: What are the fundamental forces?

- Biologist: What’s evolving/adapting?

- Economist: What are the incentives?

- Anthropologist: What are the cultural patterns?

- Designer: What affordances exist?

Temporal Lenses:

- How would someone from 1800s see this?

- How might someone in 2124 view this?

- What’s the 10-minute version vs. 10-year version?

Scale Lenses:

- Individual vs. collective

- Local vs. global

- First-order vs. nth-order effects3. Dialectical Engine (dialectical_engine.md)

# Dialectical Engine Skill

Generate productive tensions to advance thinking:

1. Thesis: State the current position

2. Antithesis: Generate strongest opposition

3. Tension Points: Where do they clash?

4. Synthesis: What new position incorporates both?

5. New Questions: What does the synthesis reveal?

Special moves:

- “Yes, and...”: Build on the idea

- “Yes, but...”: Acknowledge while challenging

- “No, because...”: Reject with reasoning

- “Maybe, if...”: Conditional acceptanceExample Flow: Thinking Session

Here’s how these elements work together in practice:

You start with confusion:

“I’m stuck on why my productivity systems always eventually fail. I set them up, they work for a few weeks, then I abandon them.”

Claude (using Custom Instructions + Assumption Excavator):

“Let’s excavate what you’re assuming about productivity itself. You said ‘systems always eventually fail’—what are you assuming a ‘working’ system means? Is it possible they’re not failing but completing their purpose?”

You respond:

“Huh. I guess I assume ‘working’ means I keep using them forever...”

Claude (activating Perspective Kaleidoscope):

“What if we looked at this through a biological lens? In nature, what systems are permanent? Most are cyclical—growth, decay, regeneration. What if your productivity systems are more like seasons than machines?”

You build on that:

“That’s interesting... so maybe the ‘failure’ is actually a natural fallow period?”

Claude (using Dialectical Engine):

“Let’s test that. Thesis: Productivity systems should be permanent. Antithesis: All systems are temporary scaffolding. What truth might incorporate both views?”

You discover something new:

“Maybe... maybe the meta-system is the ability to create new systems as needed. The failure isn’t in the system dying, it’s in not recognizing when it’s time to build a new one.”

Claude (drawing from your Thinking Patterns doc):

“This connects to your tendency to ‘optimize for efficiency vs. discovery.’ What if productivity isn’t about finding THE system but about discovering what each phase of your work needs?”

Here’s a simple way to get this setup:

The Complete Setup Checklist

Create a new Claude Project named “Thinking Partner”

Add Custom Instructions (the detailed version above)

Upload Project Knowledge Files:

Your thinking patterns and blind spots

Current questions and explorations

Conversation starters

Any frameworks you use regularly

Past thinking breakthroughs (as examples)

Install Skills:

Assumption Excavator

Perspective Kaleidoscope

Dialectical Engine

Pattern Spotter (finds non-obvious connections)

Question Flipper (transforms statements into better questions)

Create a Template First Prompt:

“I want to think through something with you. I’ll start with my rough thoughts, and I want you to help me discover what I actually think—not by giving me answers but by helping me think better. Here’s what’s on my mind: [your actual confusion]”Document Your Discoveries: Keep a running file in the project of insights gained through conversation. This becomes part of the context for future thinking sessions.

This is about creating an environment where your thinking can become sharper through structured dialogue.

The Information Theory of Meaning

Claude Shannon’s information theory was about signal efficiency—how to transmit the most information with the least redundancy. But meaning isn’t about efficiency. It’s about redundancy, about saying the same thing in different ways until understanding clicks.

AI conversation adds productive redundancy. You say something. AI reflects it back differently. You correct, refine, expand. Each iteration is the redundancy that creates meaning.

This is why those “perfect” mega prompts miss the point. They’re optimizing for efficiency when they should be optimizing for discovery.

What We’re Really Doing Here

When my grandfather learned to use a combine harvester, he developed what he called “machine sense”—knowing by sound and vibration when something was wrong. He wasn’t becoming mechanical. He was extending his human senses through the machine.

We’re developing something similar with AI, perhaps we can call it “conversation sense.” We’re learning when to push, when to pivot, when to go deeper. We’re learning to think with rather than through these systems.

This isn’t about the future of work or the automation of creativity. It’s about something more fundamental: the development of human thought itself.

Every new thinking tool (writing, printing, computing) has changed not just what we think but how we think. The difference this time is that the tool can talk back.

The Practice

Tomorrow morning, instead of asking AI to do something for you, try thinking with it:

Start with something you’re genuinely confused about

Explain your confusion as clearly as you can

When it responds, don’t evaluate whether it’s “right”—notice what it makes you think

Build on that thought with your next prompt

Continue until you’ve discovered something you didn’t know you knew

This is writing as thinking, and conversation as thinking squared. Not because AI is smart (that’s the wrong framework), but because the conversation creates a space where thoughts can form that couldn’t exist in isolation.

We’re not automating thinking. We’re developing it inside our own minds.

They’re discovered, together, in the space between mind and machine.

Talk again soon,

Samuel Woods

The Bionic Writer